Why should the ownership of capital and resources be restricted to a privileged few? Before private property, there was the commons—shared resources from nature, open to all, and ripe for the taking.

This is not a communist idea. The founders of Western thought recognized a natural, shared world beyond the arbitrary borders of kingdoms and the invisible lines of private property. From Aristotle to John Locke, they understood the concept of the commons as fundamental to human freedom and progress.

History shows us what happens when the commons are monopolized. When English lords enclosed once-free Royal Forests during the medieval period or when Pliny the Elder lamented that large estates—latifundia—ruined Italy, the result was always the same: creator societies reduced to peasant and consumer societies.

From Creators to Consumers

America is synonymous with consumerism. Many of us remember those class projects where kids depicted American culture with corporate logos plastered across their posters. But it wasn’t always this way.

Ask people about their grandparents or great-grandparents, and you’ll hear about resourceful, skilled individuals: cooks, designers, foragers, seamstresses, woodworkers, gardeners, mechanics, and carpenters all outside of whatever their profession was. Early Americans were creators, not just consumers.

Why? Because people used to be self-employed. Contract work, apprenticeships, trade guilds, and family farms flourished in an economy rich in open frontiers and unclaimed natural resources—free from monopolistic enclosures. Before the monopoly of the Bar association and accredited law schools, one could simply “read law” under a practicing lawyer like president Lincoln did.

Henry George, in Progress and Poverty, observed that the oldest civilizations with the longest-established cities suffered from the highest inequality and deepest poverty. Why? Because as land and natural resources became monopolized, upward mobility eroded, and wealth concentrated in the hands of a few.

Monopolies and the Theft of the Commons

When landlords claim the earth’s wealth, they charge high rents for resources they did not create. This extraction of wealth—rent—has historically enriched an aristocratic elite at the expense of everyone else.

From anti-colonial land reformers to Georgist single-taxers in the United States, movements have fought to reclaim the commons from rentier classes. Reclaiming the commons isn’t about destroying markets or property rights; it’s about ensuring that upward mobility and self-determination are possible for all, not just a privileged few.

The Path to a Creator Society

Reclaiming the commons today means a radical shift in how we tax and distribute wealth. The most effective approach? Abolish all taxes—except those on land values and natural resource extraction.

If a private entity wants to enclose a piece of the Earth—whether it’s Alaskan oil fields or a prime plot in downtown Manhattan—it must compensate the community for monopolizing a shared resource.

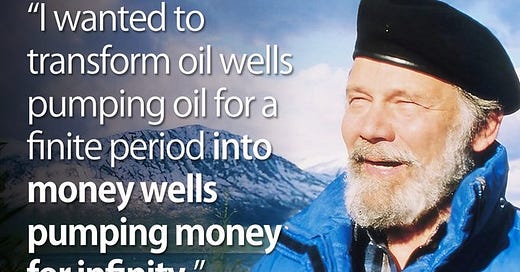

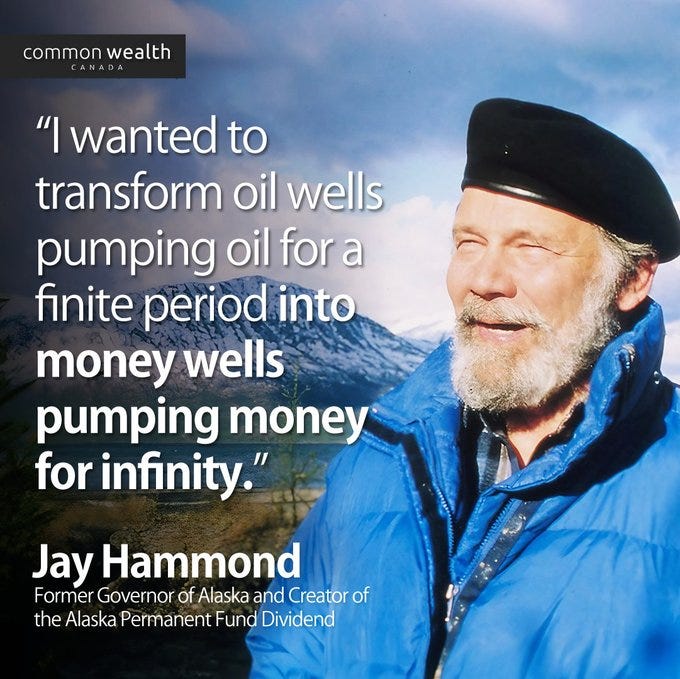

This principle isn’t new. Alaska’s sovereign oil fund pays its citizens a modest basic income from oil revenues. Cities like Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, have shifted property taxes to focus on land values rather than improvements, spurring growth and reducing inequality.

But these policies remain isolated experiments when they should be the norm.

Toward a Citizens' Dividend

Universal Basic Income (UBI) experiments show that financial security empowers people to take risks—pursuing education, starting businesses, and building better lives. A citizens’ dividend funded by land value taxation (LVT) would achieve this on a broader scale.

LVT ensures that the wealth of the commons—created by the community—is returned to the community. Land and location values aren’t created by landlords; they’re created by public investments, thriving economies, and natural advantages. Taxing this unearned wealth prevents private landlords from profiting off the backs of workers and taxpayers.

Julian Hickok wrote in The Significance of Land Value Taxation and Land Speculation:

“An analysis of the Law of Rent as applicable to investments in real estate should be made. The term ‘real estate’ includes land, which is a factor of monopoly, and improvements, which is a factor of competition. A tax on land tends to decrease the market price while a tax on improvements tends to increase the market price. The tax on land can not be shifted by the land owner. The tax on improvements must be borne by the tenant, who may or may not be the land owner. The tax on improvements may be reflected in reduction of maintenance and in curtailment of construction, which would continue until the market is sufficient to reverse the trend.”

Critics worry that some people might waste their citizens’ dividend. That’s inevitable. But LVT’s genius lies in its economic feedback loop: by taxing land values, it stabilizes housing costs, curbs inflation, and encourages productive investment. Unlike income taxes or consumption taxes, which stifle growth, LVT recycles wealth back into the economy, creating prosperity for all.

Inflation, Rent, and Stability

Today, inflation arises when private landlords capture increased productivity and spending through higher rents. LVT eliminates this by taxing away speculative land rents and reinvesting them into public goods and citizens’ dividends. The result? More money in people’s pockets and stable prices—an economy built on production, not parasitism.

The Creator Society

Reclaiming the commons isn’t just about fairness—it’s about unlocking human potential. When people are free from the crushing weight of rent-seeking monopolies, they can create, innovate, and thrive. A society where everyone has access to the wealth of the earth isn’t a utopia; it’s a return to the principles that once made America a land of creators.

What we're trying to get at here reminds me of Huey Long and his famous slogan “Every man a king, but no one wears a crown”. This is the economy we would create if no one is denied access to their birthright in the commons. As a human being and a citizen of civilization you are entitled to a share of the wealth of the Earth and a citizens dividend funded by the taxation of land values and natural resources is the ideal political program for this end.

The creator society is within reach. But to build it, we must reclaim the commons. Not just for ourselves, but for future generations, too.